By Jeff Hanns

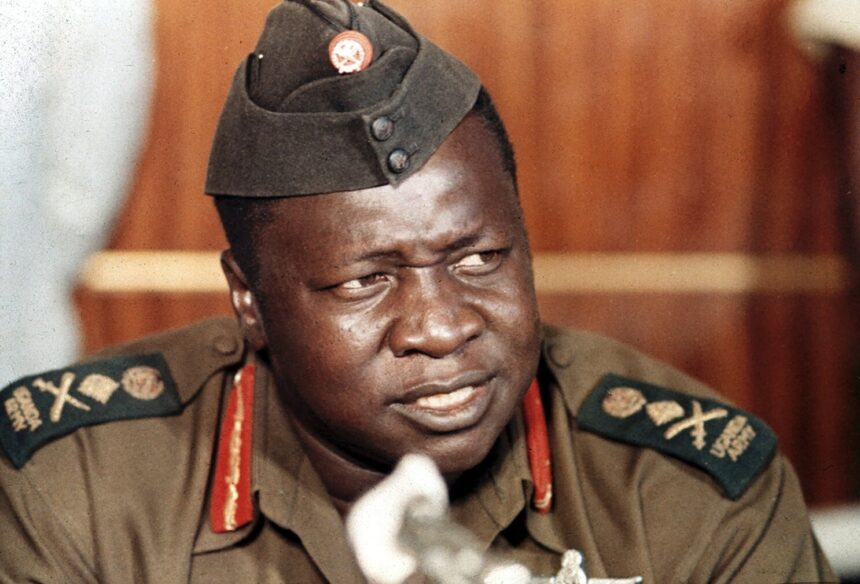

Idi Amin, known as “Big Daddy” by his supporters and “the Butcher” by his critics, rose from being a dirt-poor boy from a remote town in northwest Uganda, whose name is largely forgotten, to become the third president of Uganda and a notable figure on the global political stage. He was infamous for his ruthless repression, the expulsion of perceived traitors among non-Africans, and his widespread acts of terror, often taking pleasure in the humiliation of others. The exact date of Amin’s birth is uncertain, with

historians estimating it to be between 1925 and 1928. When Amin was born, his parents had separated, and he was primarily raised by his mother, while seeing his father infrequently. He grew up in the West Nile Province among the Kakwa people, a small Islamic tribe that had settled in the region just a few decades prior.

As a child and into his teenage years, it is reported that Idi Amin received little education due to the limited opportunities available to West Nile Ugandans. By the age of 21, he found himself with few options for the future. Rather than attempting to pursue further education, he joined the former British regiment, the King’s African Rifles (KAR), beginning the training that would come to define his future rule. Allegedly starting his career as an assistant cook, he quickly rose through the ranks, earning promotion after promotion. He was deployed to Somalia in 1949, where he helped quell the Shivda rebels, and was again deployed to suppress the Mau Mau rebellion in Kenya.

Although he was a skilled soldier, he also quickly gained a reputation for his cruelty. Amin exhibited such unnecessary brutality during interrogations that it almost derailed his military career; however, he was instead promoted to officer in 1959, achieving the highest possible rank for a black African soldier in the British military. In addition to his military prowess with the KAR, Amin was also a skilled boxer, becoming a renowned Ugandan amateur boxing champion.

His physical prowess and affinity for conflict extended into both his professional and personal life. As Uganda moved towards independence by the end of the 1950s, Amin forged a key alliance with Apollo Milton Obote, the leader of the Uganda People’s Congress. Obote would later become the Prime Minister of Uganda upon its independence. In 1962, Amin was appointed as a lieutenant in Obote’s Ugandan Army. His first order was to stop cattle theft in the north. Although he succeeded in this task, Amin committed such atrocities that the British demanded he be tried for his crimes.

Instead, Obote had him undergo further military training in the United Kingdom. Upon his return to Uganda in 1964, Amin found the army in a state of mutiny with no one in control. Tasked with restoring order, he succeeded, leading to his promotion to deputy commander. However, he was soon accused of smuggling gold, coffee, and ivory out of the Congo along with Prime Minister Obote.

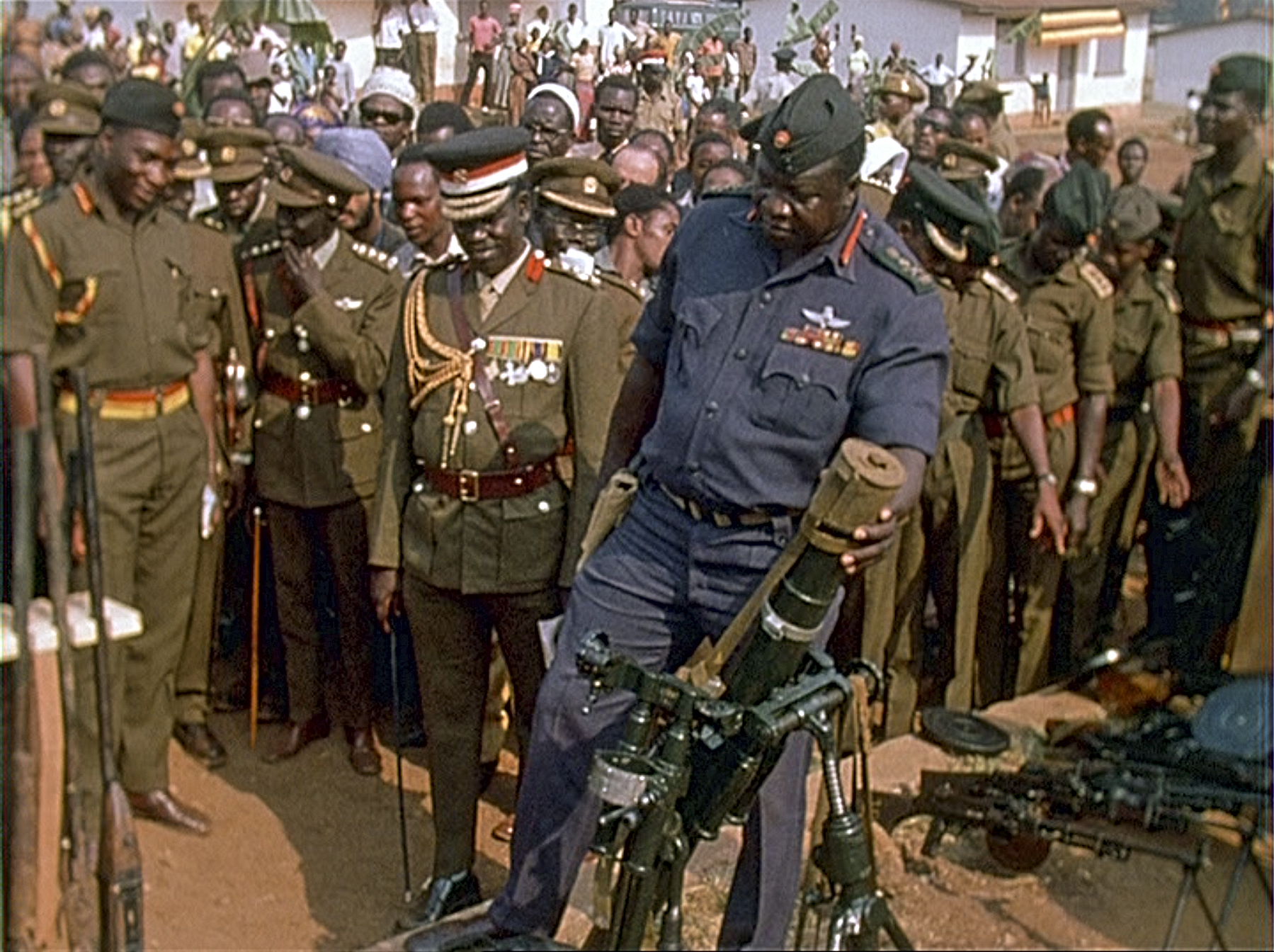

Meanwhile, in 1966, Obote dismissed the parliament and declared himself president. The lure of power fueled Amin’s ambitions, and he continued to accumulate wealth through smuggling and illicit arms dealings with Sudanese rebels, all while fortifying his position within the Ugandan military. Obote promoted Amin to chief of the Army and Air Force, granting him even greater power.

After an unsuccessful assassination attempt on Obote’s life in 1969, the president became increasingly wary and sought to tighten his control over the military in 1970. Throughout this period, Amin continued to build his network, working closely with Israeli and British agents in Uganda. Distrustful of Amin, Obote attempted to demote him, but this effort failed. Seizing the opportunity during Obote’s trip to Singapore, Amin staged a successful coup against the Ugandan government in 1971.

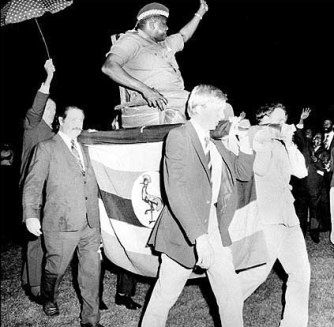

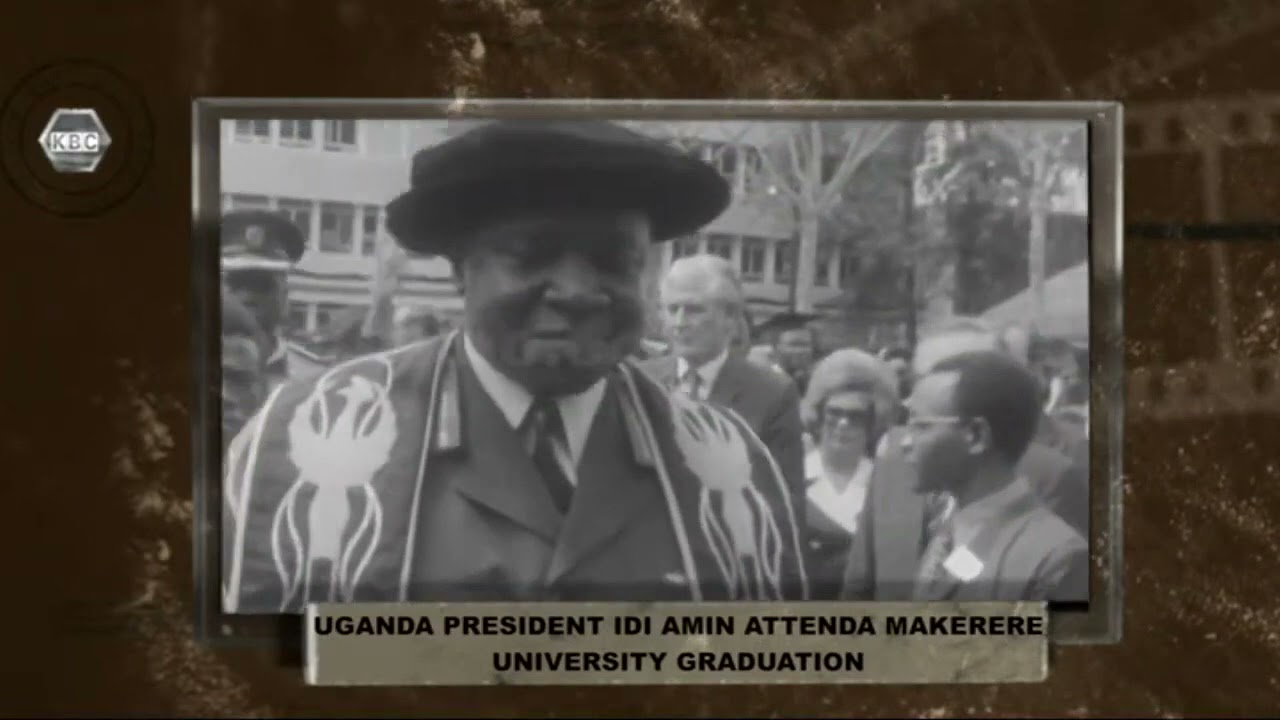

While he referred to himself as president, the title he preferred was “His Excellency President for Life, Field Marshal Al Haji Dr. Iddi Amin Dada, VC, DSO, MC, Lord of all the beasts of the earth and fishes of the sea, and conqueror of the British Empire in Africa in general and Uganda in particular.” Amin quickly began his reign of terror. In his first few months, he brutally assassinated political opponents and members of the Ugandan police before turning his attention to the general public. He swiftly dismissed the Chief Justice, the Anglican Archbishop, and the Vice Chancellor of Makerere University, among other high-ranking officials.

Within just three months, he also enlisted 10,000 new soldiers, nearly half of whom were former guerrilla fighters from the Uganda National Liberation Army, ex-Zairean freedom fighters, and those from Amin’s own ethnic group. In the first six months of his rule, violence escalated as Ugandans turned against one another, increasingly urged on by Amin himself.

From there, Amin launched one of his first major atrocities since taking power: the killing of approximately 3,000 Langi and Acholi soldiers, due to their connections with the now-exiled former Prime Minister Obote. He established killer squads within the State Research Bureau and the Public Safety Unit to hunt down Obote supporters and eliminate any opposition to his regime. Meanwhile, from his exile in Tanzania, Obote attempted to rally his followers to retake Uganda but was ultimately unsuccessful.

In 1972, Amin expelled tens of thousands of Asian residents from the country, a move that devastated the Ugandan economy and whose repercussions are still felt today. He publicly insulted leaders of the free world, including those of the United States and Great Britain, and severed Uganda’s relations with Israel, instead aligning himself with Colonel Muammar Gaddafi of Libya, as well as the Soviet Union and Palestinian groups. Despite this, and the public hostility directed at him by leaders in the US, UK, and Israel, these nations hypocritically continued to engage with the dictator.

In 1973, the United States surpassed Britain to become Uganda’s most prominent trading partner. Despite publicly closing their embassy in Kampala that same year, Amin continued to act brutally and unabated. In 1976, a group of Palestinians and members of the Red Army Faction, also known as the Baader-Meinhof Gang, hijacked a French airliner at Entebbe airport. With the support of Amin and the Ugandan army, the flight—en route from Israel to France—was held hostage by the two groups. However, Israeli forces launched an immediate counter-raid, successfully freeing the hostages.

This response sent Amin into a rage. He executed several airport employees, a number of Kenyans whom he blamed for the counter-raid, and an elderly British passenger who had been hospitalized after the attempted hijacking. By this point, Amin had earned the nickname “the Butcher of Uganda,” and he lived up to that moniker. He was responsible for the deaths of over 300,000 civilians, including high-ranking Ugandan officials such as the Anglican Archbishop, the Governor of the Bank of Uganda, and the Chancellor of Makerere University.

However, over time, Amin grew increasingly paranoid, and it became evident that his grip on power was slipping. When a group of Ugandans fled to Tanzania, he flew into a rage and accused Tanzanian President Julius Nyerere of attempting to foment insurrection in Uganda. In typical Amin fashion, he turned to military action in a bid for revenge. He sent a combination of Ugandan troops and Libyan support into Tanzania, aiming to punish Nyerere and those who had deserted. His objective was to capture the Kagera Salient, a small territory north of the Kagera River.

While he initially succeeded in taking the strip of land, it did not last long. Just two weeks later, Nyerere launched a counterattack with the help of Ugandan rebels. The momentum quickly shifted against Amin as the rebels and Tanzanian forces advanced on Kampala. Amin’s military was driven back to the capital, and when it became clear that he was not going to win, Amin fled the country. This led to the Ugandan rebels appointing Yusuf Lule as president, effectively bringing an end to Amin’s bloody reign of terror.

Amin’s retreat took him to Libya, where he lived for a decade under the protection of Muammar Gaddafi before eventually moving to Saudi Arabia. He spent the remainder of his days there until he died in 2003, never held accountable for the crimes he committed.